The sun had yet to rise on this November morning. With temperatures hovering in single digits and a 40-mile-per-hour wind in my face, I hoped the hunt would end fairly quickly, and figured it would. After all, how hard could it be hunting bison on a 10,000-acre ranch on horseback?

Slinking closer to the edge of a cliff, I spotted the unmistakable stature of a bison. It was alone and in the bottom of a deep canyon. The big bull grazed 300 yards away in a spot that would take the better part of an hour to reach on foot.

Scooting forward to sit and watch the bull, our movement on the skyline alerted it. The instant the bull busted us, it went on the run. Before we knew it, the bull disappeared over the horizon, more than a mile away, still running at full speed.

I turned to head back to the horses when Jason called me back. “Hey, walk right up there and look over the edge,” he said. Moving to the edge of a sheer cliff, my stomach turned. “It’s straight down,” I thought out loud. “This is a traditional jump-off, where the Native Americans used to hunt bison,” Jason shared.

I stood there, staring, unable to say a word. My mind wandered, envisioning what it must have been like for the Indigenous peoples to drive herds of bison off the edge of this very cliff, sending them to the bottom, where hunters finished them off with handmade spears and bows and arrows.

“It’s a powerful feeling, isn’t it…standing where hunters hundreds of years before us pursued the same animal we’re after today,” Jason asked solemnly, snapping me from a daze.

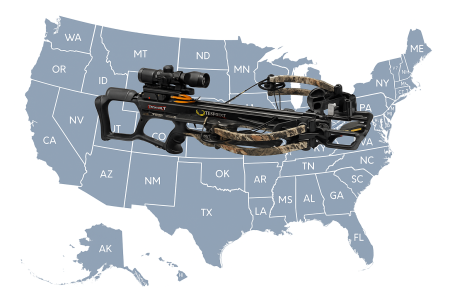

I’d hunted bison twice before, both times on private land. My first bison hunt was with a rifle. My second was with a compound bow. Both hunts were fun and memorable. In my home state of Oregon, crossbows are prohibited, so when the opportunity came to again hunt bison (this time using a TenPoint crossbow), I jumped at the opportunity.

Like many hunters, bison have always intrigued me. I applied for free-range tags in three states for many years but never drew a tag. Bitten by the bison bug and all that comes with hunting them on the open plains, it was fortunate that this time, I hooked up with a friend who had run hunts on a private ranch for several years.

Shortly after my hunt, the ranch sold and the bison hunts no longer take place there. However, there are many private land bison hunts, including hunting them on horseback and camping in covered wagons each night.

In the location where we hunted, bison once roamed freely in mind-boggling numbers. Here, there are prevalent traces of bison bones that are hundreds of years old, left from the ones who roamed freely, as well as traces of the Native Americans who depended on them. The teepee rings, arrowheads, and rock art found in this region are captivating and made lasting impressions on me.

I had bison to thank for bringing me to this place. Pursuing them on horseback made the hunt even more special. By midday, Jason and I had covered a few miles on horseback. We came across a trio of bison, made a stalk, got to within 25 yards, but never got a shot before they busted us and bolted through a rugged ravine. We searched but never saw them again.

We stayed high atop the windy ridges, hoping to spot bison in the protected ravines, below. From there, we’d make a move. It was Badlands hunting at its finest, and we saw some monster mule deer along the way. The mule deer were spooky, as expected, but so too, were the bison. The buffalo would routinely flee at the first glimpse of danger, and they would move fast. I underestimated them. This wasn’t a ride and shoot ‘em hunt; this was bison hunting as I’d hoped to have.

With less than an hour of daylight remaining, Jason and I spotted another bachelor group of bulls. On my previous bowhunt for bison, I took a giant bull. This time, I wanted a young bull, one about two to three years old that would be good eating for the family. Finally, we found what we were looking for.

Leaving the horses tied atop a ridge, we slithered down a ravine and got out of sight and downwind from the bulls. Snow had been falling throughout the day, making the gumbo mud difficult to traverse. The clay sticking to our boots was so slippery it was like walking on ice at times. This made the going slow, and I had doubts we’d even be able to reach the bulls by dark.

“They should be right over the top,” whispered Jason, as we paused on the backside of a knoll. Bolt in place, monopod erect, I edged to the top of the knoll. The bison were nowhere to be seen. Sitting at the ready, I waited, and finally, three bulls fed out from behind a mud spire that had been carved by wind and rain. They were 40 yards away, but I didn’t have a shot at the bull I wanted.

As soon as the bison moved out of sight, I clawed my way up another gumbo hill. Intense winds slammed me in the face. Eyes watering, face numb, I knew it was now or never as only minutes of daylight remained.

Following the bison’s tracks, I inched over another knoll. Hoping to catch them on the opposite hillside, I was surprised to find them more than 100 yards away, smack in the bottom of a deep-cut draw. With no trees in sight, the bison were out in the open—and so was I.

Finally, the three bulls emerged. The shot angle wasn’t perfect but given the speed with which the TenPoint XXModel NameXX moved my bolt, the stability offered by the monopod, and the impressively tight groups it was shooting, I slowly squeezed the trigger.

The bolt hit the mark, disappearing behind the last rib of the bull as it quartered away.

The bull went a short distance and piled up. The 100-grain titanium broadhead was buried in the offside shoulder and it did its job, fast. Field dressing the bull, I couldn’t help but imagine what it must have been like for the Native American hunters in this area to tackle such tasks during their time, with none of the modern tools we have today.

It was the perfect end to a great day, and I had the bison to thank for bringing me to this historically rich part of North America. While private land bison hunts might not be for everyone, they’re an option for those who, like me, have poor luck drawing public land tags in the lottery. And in the end, you’ll fill your freezer with some of the best-eating game out there.

Free-Range Bison Options

There are some great, free-range bison hunts in the U.S., but the chances of drawing a tag can be hard to come by. That said, someone has to be awarded a bison tag, and it could be you.

Utah offers bison hunts in the Book Cliffs and Henry Mountains. These hunts can be very demanding, and tags are once-in-a-lifetime opportunities. The cost of a non-resident bison tag is $2,200, plus $72 for a license. A bison tag on famed Antelope Island is $2,615.

Wyoming offers the easiest free-range bison hunt, physically speaking, as it is centered around the outskirts of park systems.

The challenges here are drawing a tag, then hoping the bison leave the park and go to the public lands during the time of your hunt. The cost of a non-resident bull bison tag is $4,402 and a cow/calf tag is $2,752. There’s an application fee of $15.

Alaska has some good bison hunting opportunities and the most affordable tags, but you need to understand that the costs of getting in and out of a remote hunting area, (especially with a one-ton animal to bring out) can be expensive. I lived in Alaska for years, but never drew a tag. The Delta Junction herd is most easily accessed and offers the highest success. A tag for a non-resident bison hunt is $90 plus $160 for a license.

Per our affiliate disclosure, we may earn revenue from the products available on this page.